In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field: books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Robert E. Howard is often deservedly acclaimed as the father of the sword and sorcery genre. His most widely known creation is Conan: a barbarian turned thief, pirate, warrior, military commander, and then king. (I reviewed a book of Conan’s adventures here.) But before Conan, Howard created another barbarian turned king—the character of Kull. While the characters certainly share similarities, and are both mighty warriors who cut a bloody swath through their worlds, Kull’s adventures have a distinct aura of mysticism, magic, and mystery that makes them compelling in their own right. And of all the characters Howard created, Kull is my personal favorite.

The Kull stories marked the first time that Howard created an entire quasi-medieval world from whole cloth. While the various races and tribes bear some resemblance to peoples who inhabit the world today, he portrayed a time before the great cataclysm that caused Atlantis to sink, when even the shape of the land was different, a time when pre-human races still walked the Earth. Kull is an Atlantean barbarian who from his earliest days harbored an ambition that set him apart from his fellow tribesmen. A large, quick man, often compared to a tiger, he is powerful yet lithe, with dark hair and grey eyes, and a complexion bronzed from a life in the sun. He had been a warrior, galley slave, pirate, mercenary, and general before seizing the throne of Valusia from the corrupt King Borna. While a mighty warrior, Kull also has a whimsical and inquisitive side. He could be kind and sensitive, and is fascinated by the metaphysical.

Buy the Book

Warrior of the Altaii

Kull has another unique element to his personality in that he was presented as asexual, uninterested in sex in any form. Some speculate that Howard may have still been a virgin when writing Kull’s adventures. Or perhaps, because thinking of the time held that men’s strength was diminished by sex, the choice represented an attempt at portraying a more powerful character. In any event, the depiction marks Kull as different from many other warrior characters of the time, and distinctly different from Howard’s Conan. Ironically, while the King of Valusia was not interested in sex, a large number of his adventures were set in motion by subjects who wanted to marry for love, rather than follow the country’s traditional laws and customs.

Kull was one of Howard’s earliest creations, and only three of his adventures saw print before Howard turned to other characters: “The Shadow Kingdom” and “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune,” which appeared in Weird Tales in 1929, and “Kings of the Night” which featured another Howard character, Bran Mak Morn, battling Roman invaders, with Kull magically appearing to assist his descendants.

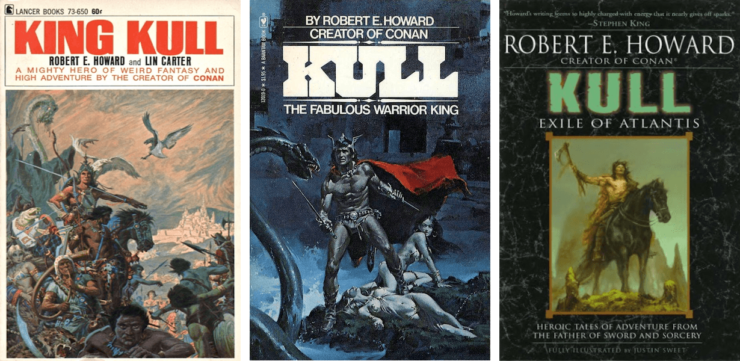

There were a few other Kull stories written and never sold, and some unfinished fragments as well. But even if you include every Kull tale ever written along with all those fragments, they’d fill only one slim volume. There had been some Kull stories included in collections over the years, but most people’s exposure to Kull was the paperback collection King Kull, edited by Lin Carter and released by Lancer Books in 1967, during a period when the fantasy genre was growing by leaps and bounds and publishers were hungry for tales in this vein. The Lancer edition collected all the Kull tales, but has sometimes been criticized because Carter rewrote some of the stories and finished the fragments (similar to what L. Sprague de Camp did with Lancer’s Conan volumes).

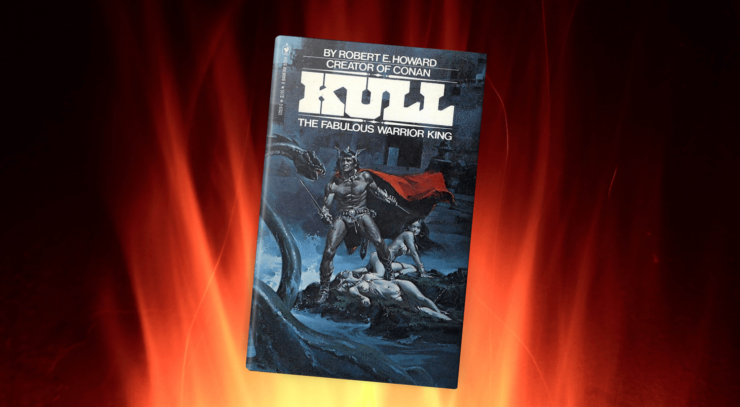

My review in this column is based on a collection issued by Bantam Books in 1978, introduced by Andrew J. Offutt. As far as I know, this was the first book that presented Kull’s adventures, fragments and all, as Howard wrote them, without alteration.

I also own a more recent volume, Kull: Exile of Atlantis, published in 2006 by Del Rey Books. This volume is part of a handsome collection of Howard’s work in its original form, which features Conan, Bran Mak Morn, Solomon Kane, as well as other assorted Howard tales. The stories are presented with historical notes, interesting commentary, and are illustrated throughout.

About the Author

Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) grew up in Texas, and started his professional writing career at the age of 18 with a sale to Weird Tales. While Howard was sensitive and given to quoting poetry, he was also a boxer and valued physical strength. By age 23, he was able to quit his other jobs and write full time. While he is considered to be the father of the sword and sorcery genre, he wrote in many other genres as well, including suspense, adventure, boxing-related fiction, horror, westerns, and even planetary romance. Howard created many classic characters, including Kull, Conan, Celtic king Bran Mak Morn, Puritan adventurer Solomon Kane, and boxer Steve Costigan. He created an elaborate ancient history of the world which included the mythical Pre-Cataclysmic and Hyborian Ages, giving a solid foundation to his fantastic tales. He also wrote stories based in the Cthulhu mythos.

Howard was close to his mother, who encouraged his writing but also suffered from tuberculosis throughout his life. In the final year of his life, he hit a rough patch in his career where there were late payments from Weird Tales, other markets were drying up, and it seemed like his disappointments were outnumbering his successes. His mother was nearing death, and when he was told she would not recover, he committed suicide. His writing career ended after only 12 years, and Howard never saw his greatest success, which occurred long after his death.

Kull in Other Media

Kull’s most frequent appearances in other media were in the pages of comic books. My favorite of these were the original run of Marvel comics, which began in 1971. The artwork for these adventures was beautiful, with the talented Marie Severin doing the penciling and her brother John Severin providing the inking. It stood out from other Marvel works with an intricate style that reminded the reader of Prince Valiant rather than Jack Kirby’s flamboyant superheroes. There were other appearances in Marvel comics over the year, but none matched those initial books. Kull was then licensed by Dark Horse comics starting in 2006, and most recently by IDW starting in 2017.

There was one movie appearance by Kull, the rather mediocre Kull the Conqueror, which appeared (and quickly disappeared) in 1997. It is reported that the film was originally intended to be the third installment of the Conan franchise starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, and was loosely based on the Conan story “The Hour of the Dragon.” The Conan movies had already borrowed elements from the Kull stories, including the villain Thulsa Doom, so converting this new one to a Kull story was presumably not too difficult. Kevin Sorbo starred as Kull, and while he is a personable actor, my recollection is that he was not terribly convincing as the moody Kull, and Tia Carrere, starring as the evil Akivasha, did not fare much better. There was reportedly a lot of studio meddling behind the scenes; moreover, the Kull name was not as well-known as Conan’s, and in the end the film did not do well at the box office.

Kull: The Fabulous Warrior King

According to the copyright page, this book contains all of Kull’s stories with two exceptions, ones in which Kull appears as a supporting character in tales with more modern settings. These include “Kings of the Night,” a Brak Mak Morn adventure where Kull appears from the mists of time to aid his descendant, and “The Curse of the Golden Skull,” a story partially set in modern times.

The book begins with an introduction by author Andrew J. Offutt, who like me, is a fan of Howard’s work, and considers Kull to be his favorite of all Howard’s protagonists. This is followed by a short prologue that describes the world at the time of Kull, with barbaric Atlantis and the Pictish Isles in the western ocean, civilized but decadent nations on the main continent, and mysterious lands to the east and south. Then we get “Exile of Atlantis,” the only Howard tale that shows Kull before he becomes a king; a short story that reveals the incident that drove Kull from his tribe. Rather than allow a young woman be tortured for marrying a man outside her tribe, Kull gives her a quick and merciful death, and then has to flee for his life.

“The Shadow Kingdom” is Kull’s greatest adventure, and my favorite fantasy story of all time. This is the first Kull adventure ever published, and I have always admired the way Howard presents the characters and the Kingdom of Valusia so evocatively, and with such economy. Kull is approached by a Pictish emissary—a fellow barbarian who immediately irritates him—who invites him to meet with the ambassador Ka-nu. There, Kull learns of a plot against him, and is told that someone will be sent to aid him, wearing a distinctive bracelet. The man who arrives is the emissary who irritated Kull, Brule the Spear Slayer. Brule tells him that an ancient race of snake-headed people who can take human form plans to kill Kull and replace him with one of their own. Kull has always felt that his courtiers wore masks that concealed their true emotions, not realizing that the truth was even more sinister. What follows is a twisting and turning tale of deception, ghosts, monsters, and death, culminating with a fierce and exciting battle where Kull and Brule stand together against a score of snake men, forging a friendship that will last a lifetime.

“The Altar and the Scorpion” is a vignette where Kull is mentioned but does not appear, and evil upstart priests learn that it is not safe to disregard the most ancient of gods.

The story “Delcardes’ Cat” is an interesting one. Here we see Kull’s interest in the metaphysical, as he encounters a young woman with a talking cat that has the powers of an oracle. Kull is so intrigued that he moves the cat into the palace. When the cat tells Kull that Brule has been swimming in the Forbidden Lake and has been dragged under the water by a monster, Kull believes, and rides off to the rescue. The lake is home not only to strange beasts, but also a mysterious city of ancient beings. Kull survives this surreal experience and returns to find that the cat only speaks due to ventriloquism, and when the slave who always accompanied the cat is unmasked, he finds an evil skull-faced necromancer: Thulsa Doom. This story is frequently compelling, but is all over the map in terms of tone and structure, and I’m not surprised it remained unpublished until after Howard’s death.

“The Skull of Silence” is the name of an abandoned castle in Valusia, where an ancient hero supposedly entrapped the spirit of absolute silence. Kull decides to visit, and a compelling and evocative story ensues in which Kull battles an elemental force into submission. The prose is lurid, but the tale is compelling.

“By This Axe I Rule!” is my second favorite Kull story, a tale of an attempted assassination and coup. When it did not sell, Howard added mystical elements and changed the protagonist, with the story becoming “The Phoenix on the Sword,” the first Conan story. I personally prefer the original version, as the musing on the royal prerogative versus standing law is very much in the vein of other Kull stories. There is also a sweet scene where Kull in disguise speaks with a young girl, and gets a glimpse of how people really see him and his rule. And the scene where Kull is cornered alone, facing a squad of assassins, is a favorite of mine, ranking right up there with the desperate fight in “The Shadow Kingdom;” a moment that captures his barbaric essence:

Kull placed his back to the wall and lifted his axe. He made a terrible and primordial picture. Legs braced far apart, head thrust forward, one red hand clutching at the wall for support, the other gripping the axe on high, while the ferocious features were frozen in a snarl of hate and the icy eyes blazed through the mist of blood which veiled them. The men hesitated; the tiger might be dying, but he was still capable of dealing death.

“Who dies first?” snarled Kull through smashed and bloody lips.

“The Striking of the Gong” is another metaphysical tale, where Kull has a brush with death, and gains a glimpse of what lies beyond our universe.

The story “Swords of the Purple Kingdom” is a rather straightforward adventure tale where a young couple from different nations asks Kull for permission to marry. Kull is then kidnapped in a coup attempt, and coincidentally taken to the same garden where the young couple were going to meet and elope. When the young man helps Kull fight off the bandits, he finds Kull much more sympathetic to his romantic situation. My only criticism of this story is that the fight scene is a bit too similar to those in earlier stories, and the “young lovers defy tradition” plotline is also wearing a bit thin.

“The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune” is another of the metaphysical tales, with Kull lured into viewing mystical mirrors that lead him to doubt his very existence. This is followed by a poem, “The King and the Oak,” which has Kull battling an ancient and malevolent tree. “The Black City” is a very short fragment that seems to be the start of a tale: Kull is visiting a far-off city only to have one of his Pictish guards kidnapped, and another die of fright.

The next fragment features Kull becoming enraged by a young foreigner who elopes with a Valusian girl of royal blood, taunting the king as they escape. Kull gathers his troops and rides in pursuit, without heed for the potential consequences. The tale takes a metaphysical turn when the expedition reaches the river Stagus, the boatman carries them across, and Kull’s troops prove willing to follow him into what appears to be Hell itself.

The final fragment portrays a board game between Kull and Brule, seemingly the start of yet another adventure. And the book ends with a historical summary of the time that elapsed between the times of Kull and Conan.

Final Thoughts

And there you have it: a summary of every classic adventure undertaken by Kull, the barbarian king. Unlike Conan, whose entire life was chronicled by Howard, we only get glimpses of this compelling character. But those glimpses include some of the most interesting stories and exciting scenes that Robert E. Howard ever wrote.

And now that I’ve said my piece, it’s your turn to chime in: Have you read any of Kull’s adventures? If so, what did you think of them? Were you one of the few who saw the 1997 movie? And in your opinion, how does Kull stack up against Conan, and the other great heroes of sword and sorcery?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

My first* exposure to Kull was the Donald M. Grant hardcover with illustrations by Ned Dameron. I assume the text was the same as the 1977 version rather than based on the Carter completions?

The Del Rey is the best place to read Kull, but this is my favorite version to look at.

*I had previously read at least one Kull story — “Swords of the Purple Kingdom” — in Lin Carter’s Realms of Wizardry anthology.

I haven’t read any Kull stories, but I devoured the Ace Fantasy reprints of the Conan books in the early ’80s. I’ve never read the unadulterated REH texts, only the L. Sprague de Camp versions, so I can’t compare, but I greatly enjoyed what I read at the time. Thanks for all the info on Kull. It has inspired me to track down these stories and revisit REH’s work in general.

Like many people, my first experience with Kull were the 1970s Marvel Comics adaptations. Your comparison of Marie and John Severin’s art to that of Prince Valiant is spot on.

After the Marvel versions, I read every REH paperback I could find.

Worms of the Earth, featuring Pictish King Bran Mak Morn is probably my favorite REH story.

I was never a KULL fan, stuff like this give you that second look

Found the Lancer collection when I was 13 and it was then pretty good. But it didn’t quite stick with me like Bran Mak Morn, which I got about then too.

Years later, questions arose–why weren’t the serpent men reptilian all the way down instead of just their heads? Why should a giant slug (in that Kamula story) be grateful to be killed? Why, when you want to seal a door shut, do you jam a sword into it–that seems like a waste of good weapons. And why couldn’t Lin Carter write his way out of a paper bag? All those italics….Anyway, it was fun when I was a kid.

@1 I love those illustrations. Thanks for sharing them; I had never seen them before.

The Bantam Kull collection came out just as I was discovering REH. I loved the Kull stories because of their more mystical, supernatural side. Some of them would fit nicely beside Moorcock’s early Elric short stories. Conan’s Hyborian Age became a bit too familiar with all the non-REH novels published over the years. Kull’s world retained an air of mystery. It’s surprising that so little was done with the character over the years. Even Cormac mac Art got seven books.

@6: You’re welcome! The book actually has I think 20 full-color illustrations, so if you get a chance it’s worth checking out for the art, at least.

I don’t know if I enjoy the Kull stories more than Conan, but definitely just as much.

I came across a paperback version of the Del Rey book for cheap and figured it would be just like Conan but worse. I was wrong. Kull is more serious and melancholy and his stories have a different focus.

I think “By This Axe I Rule” is my favorite. I also prefer it over Phoenix. The end scene gives me chills every time and is much more effective than what Howard changes it to for Conan.

Yes, I have read all the Kull stories, no I did not see the movie because…I found him a much less interesting character than Conan. I found his philosophising incongruent with his background, and—as with you—I got tired quickly of the marriage plot device. Conan forever

Don’t avoid the movie because the character in the stories is less interesting than Conan in the stories.

Avoid the movie because it’s altogether terrible. And not even terrible in an interesting or entertaining way — just all-around meh. With some truly wretched late-90s CGI at the end.

Though one interpretation might be that Kull was ‘uninterested in sex in any form’, I don’t recall the Kull stories ever stating such. Granted, Kull strikes quite a contrast with Conan who was often driven to foolish and rash action by his libido. Kull was more likely to find himself in trouble because of his curiosity in the metaphysical.

Looking at all those covers I am inclined to wonder why Kull the Warrior King was unable to acquire any clothes.

I never really got into Kull, he always seemed less melancholy and more whiny. Like, Conan at least enjoyed being king, what with the gold and the royal brothel next door, and had friends among the court. Kull had no friends besides Brule, and can barely manage a working relationship with Tu. One story Tu’s spendthrift nephew sells out the kingdom and Kull to assassins; Kull kills the guy, then moans about Tu not paying the kid’s gambling debts.

While l am a huge admirer of Robert E. Howard – a gigantic talent and phenomenally, supremely gifted storyteller – and a huge fan of the character and stories of Conan (my favorite being ‘Red Nails’), l have always considered Kull to be my favorite Howard character by far, and actually prefer both him and his stories to those of Conan. Kull, l believe, is a far more interesting individual than Conan, and, while being every bit as fearsome a warrior as Conan, has a more intellectual, serious aspect that to me gives him more intrinsic depth and makes him more relatable and appealing. The Thurian Age world of Kull’s time is much less defined and fleshed out as compared to Conan’s Hyborian Age, which lends it an air of grim mystery and the dark unknown that is endlessly intriguing. I think it is also an even more inherently dangerous world than Conan’s as well, with dark magic being even more prevalent and commonplace and the remnants of pre-human and nonhuman enemies of the human race still lurking just about everywhere in relatively large numbers. The more ‘dreamlike’ nature of the stories reflect the more surreal and paranormal aspect of the world itself in Kull’s time, very deep in prehistory, about a hundred thousand years in the past, as compared to Conan’s, which is much closer to our own known history at about 12,000 years ago. In addition, l personally find the Kull stories to be Howard’s best and most deeply sophisticated writing of all – l never tire of reading and rereading my absolute favorites, ‘The Shadow Kingdom’ (in my opinion the single greatest fantasy/sword & sorcery story of all time), and ‘By This Axe I Rule!’. Also, it will never cease to utterly amaze me that Howard created and wrote all that he did by the tender age of 30 – a tremendous output of superlative storytelling spanning multiple genres – fantasy, horror, adventure, westerns – in a mere 12 year span, and at such an unbelievably young age. Absolutely, positively incredible. And a final note – l find comparisons of Kull and Conan to be somewhat silly and pointless. I believe Howard would have made it very clear that the two men are complete equals both physically and in terms of combat prowess in every respect, although l suspect that, owing to his personal history, Kull may very likely have had more extensive formal and military training in arms, while Conan’s style of fighting may be somewhat more instinctive and unconventional. One also has to remember that in Conan’s time, Kull is widely regarded as a demigod, a legendary warrior king who pretty much single-handedly thwarted and crushed the resurgence of the Serpent Men and, with battle axe in hand, actually wiped them out of existence – a titanic feat which could only be accomplished by someone of unimaginably forceful, totally indomitable will and colossal physical ability. That someone is the magnificent and incomparable King Kull, in my opinion Robert E. Howard’s greatest and most interesting creation.